|

Patrick Plattet

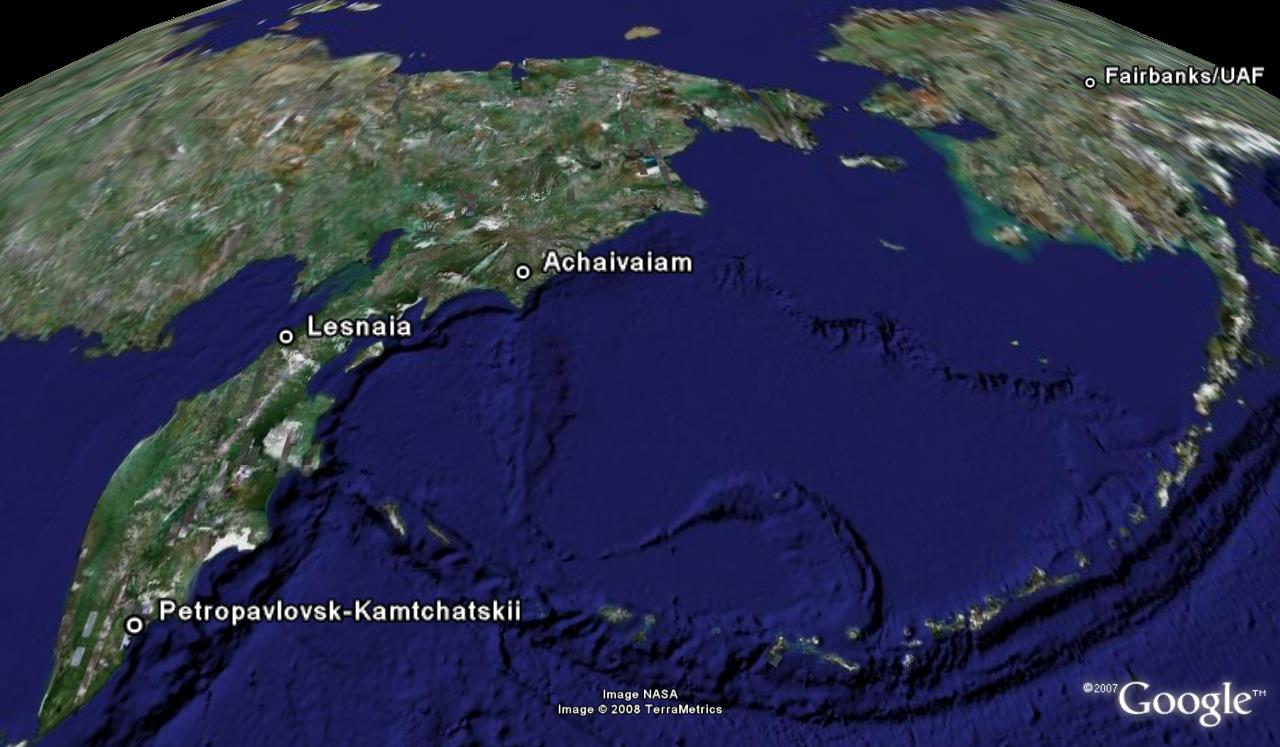

Carried out from the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF, Dept. of Anthropology), my research led to the realization of new fieldwork in Kamchatka (September 2006 – March 2007) during which my interest was focused on the modes of representation of religiosity in contemporary urban (Petropavlovsk-Kamchatski) and rural areas (Lesnaia, Achaivaiam).

Since returning from the field, I am trying to identify supports of “religious feelings” and how these feelings/aptitudes relate (or not) to a religion in particular, to the multiethnic and multicultural social fabric of the Kamchatka peninsula, to a specific sense of insular identity and of remoteness, to an officially sanctioned Kamchatkan mythology, to the memory of collective and individual revolts and rebellions (against colonial power), etc. My main focus extends to the ritualized behaviors which at the same time frame and underlie the various expressions of religiosity.

In Petropavlovsk-Kamchatski (P-K), the capital of Kamchatskii Krai, I mapped the new supports of religiosity that have emerged since the late 1990s at key places of the public space. The anchoring of these religious markers at specific crossroads of P-K helped me illustrate the phenomena of historicization, merchandization and politicization that affect the construction of religiosity in today’s urban Kamchatka.

|

| Giant

screen broadcasting video messages from the Episcope Ignatii at the

“Place of the Victory,” next to the city’s main open market (P-K,

October 2006) |

|

|

| Memorial monuments rehabilitating Orthodox historicity in the Russian Far East on the “Lenin Place” (P-K, October 2006) |

Construction

of large-scale buildings for an Orthodox Cathedral (and further on the

same street for an Evangelical Church) along the unique road axis that

goes across town (P-K, February 2007 |

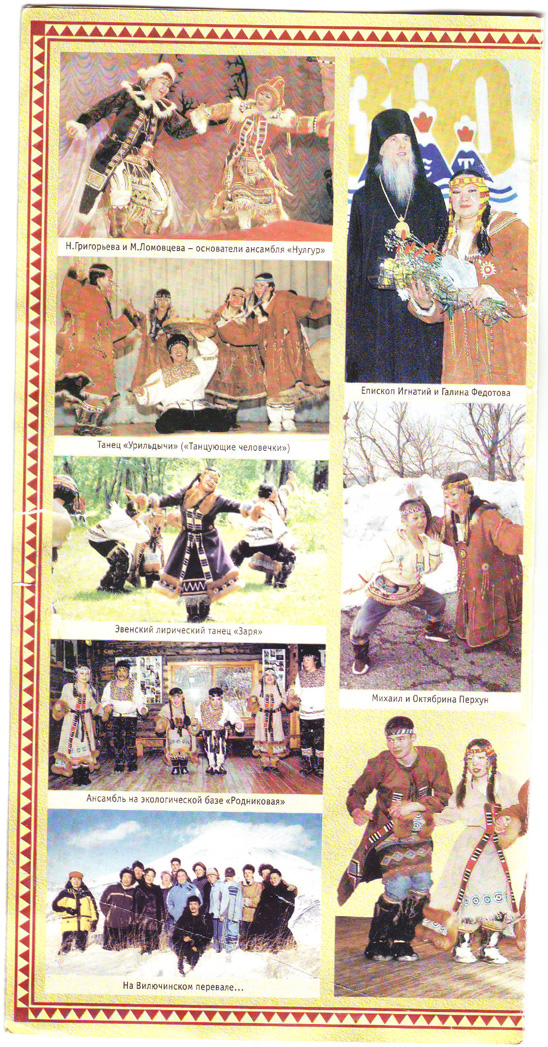

In parallel, I have also analyzed the “modern” works of official artists (and their subjective relationships to them), showing how Orthodox Christianity is instilled in the artistic representations of indigenous religious experiences and how this process is subordinated to the religious variant of the myth of the “brotherhood of Kamchatkan peoples.” In Kamchatka, the recycling of this Soviet myth (and the production of its by-products) is a recurrent feature of both the Orthodox and the Evangelical nebulae. In each case, it goes along with the definition of a “ritual orthodoxy” which reveals the acceptable outcomes of religious “encounters” in the Russian Far East.

Inverted perspective: “Traditional” Kamchatkan garments decorations decorated with iconic representations of Jesus and Maria |

|

| |

Volcanoes,

Russian Orthodoxy and Indigenous Dances: representing the “soul” of

Kamchatka (brochure presenting the National Even Dance Ensemble

“Nulgur”) |

Having shown during the second Newrel workshop how Orthodox and Evangelical Churches managed to developed distinct strategies for missionizing different zones of “religious darkness,” I am currently analyzing forms of popular religiosity in rural areas that are under Evangelical influence (Lesnaia) by comparing them with other forms that have developed out of any external religious control (Achaivaiam). My intermediary conclusion is that, far from devastating the creative forms of religiosities elaborated since the turn of the 18th century, Evangelical activism in Lesnaia (and the resistance to it) contributed to revitalize the village “hunting” society as a whole after the predicament of the 1990s. Without neglecting the tensions and the conflicts that followed the Evangelical wave in Northern Kamchatka, my point is that “Faith/Gospel Movements” favored the reintroduction of a plurality of religious specialists, a pattern that had been dominant in Lesnaia until the 1940s and the closure of the Orthodox chapel by the Soviet authorities. In an article in preparation with Virginie Vaté, I suggest that the presence of various religious specialists (be they shaman, blacksmith, priest, pastor, elder, etc.) plays an important role in the processes of social integration and of cultural transmission. Special attention to the ritual altars periodically fabricated in Lesnaia relates this view with the modes of ritual actions mobilized by each category of specialists in order to represent their religiosity. Here, my argument is that the fabrication of ritual altars (for funerary, hunting or theatrical purposes) not only reveals the integrating ability of the local religious system but also manifests an act of “social cognition” that informs us about the relevant modes of representation of religiosity. A second article exploring this theme is in preparation.

|

|

| Funerary altar: supporting the “Orthodox” representation of a dead person (Lesnaia, January 2007) |

Hunting altar: supporting the “shamanic” representations of big game animals (Lesnaia, October 2006 |

|

| Theatrical “altar”: supporting the “Evangelical” representation of Koryakness (Lesnaia, January 2007) |

|